Artist Spotlight: Abigail Jacqueline Jones

Abigail Jacqueline Jones is a performance artist, writer/storyteller and illustrator based in east London. This week, we caught up with Abigail, who is currently a studio holder at our Stratford Studios, to find out more about her practice and her new project ‘The Gender Chest’ which is designed to support young transgender people through the process of coming out in school and family contexts.

Can you tell us a bit about your work as a performance artist, writer/storyteller and illustrator? How do you maintain these separate but overlapping practices?

My practice is strongly rooted in using fiction to discuss and raise awareness of a variety of social issues, predominately surrounding gender and class-based dynamics, as well as attitudes towards society, economy and imperial history under a conservative-leaning British Establishment. Performance and illustration are naturally intertwined with the history and practice of storytelling. In many ways, my work seeks to take these elements and use them to produce a fully immersive, interactive manner of experiencing a story that goes far beyond the simple acts of reading or listening. I want to enable the audience to fully connect fiction and narrative to the people, places and social dynamics that inspired them.

My current work is centred around producing a long-form piece of adventure fiction titled ‘This Damned Metropolis & Capital’, which focuses on a community of young slum-dwellers living in an abandoned theatre off Drury Lane. One of the last surviving West End slums, the characters battle to protect their home and community from the threat of destruction, using the displacement of poor Londoners from their neighbourhoods throughout the 19th and early 20th century as an allegory for contemporary gentrification and the dynamics of modern socio-economic inequality. Aside from publishing the book as a hand-illustrated collection of zines, released chapter-by-chapter, I will also be putting on a series of walking tours, treasure hunts, public performances and readings based on the story. These will be on location at various sites across London, hoping to fully immerse my audience in the tale and keep their interest piqued and excitement palpable as they await the next episode.

You’re currently working on a charitable project designed to help transgender children and adolescents through the process of coming out in school and family environments. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

The project – under the working title of ‘The Gender Chest’ – is designed to decentralise access to a whole host of resources created to assist transgender children, adolescents and young adults. Navigating the extreme challenges of coming out as trans and beginning social and medical transitions is hard, and the project aims to make these resources more easily accessible, especially to those who might not live in close proximity to major cities which tend to have more developed, longstanding queer communities and support networks (such as London or Brighton). Others might struggle to access support networks regardless of where they live, due to anxiety around attending queer support groups in person, difficulties travelling or school/work schedules getting in the way. ‘The Gender Chest’ itself will take the form of a shoebox, decorated with art produced by me and various collaborators, and will contain the following:

• Advice on how to write a coming-out letter addressed to those closest to the Box’s owner, including template phrases they could use as launching-off points if writing an entirely original letter is too stressful.

• A small collection of illustrated booklets featuring: legal and medical advice; educational information regarding medications, the functions of sex hormones and the physiological and psychological changes they can produce, and the variation in their effects caused by genetics; advice on how to go about purchasing identity affirming items such as clothing (in particular, clothing specifically made for trans bodies, or made for taller women/shorter men or boys); how to deal with shopping in store departments intended for the ‘opposite sex’; and a ‘checklist/timeline’ page where the Box’s owner can note down any combination of steps in transition they wish to take, and tick them off once completed.

• An illustrated glossary of terms and terminology relevant to queer and transgender issues.

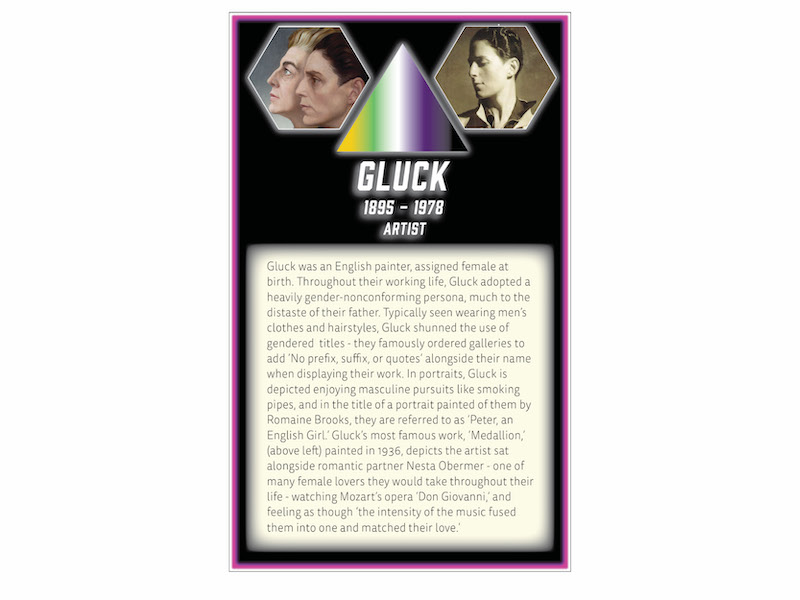

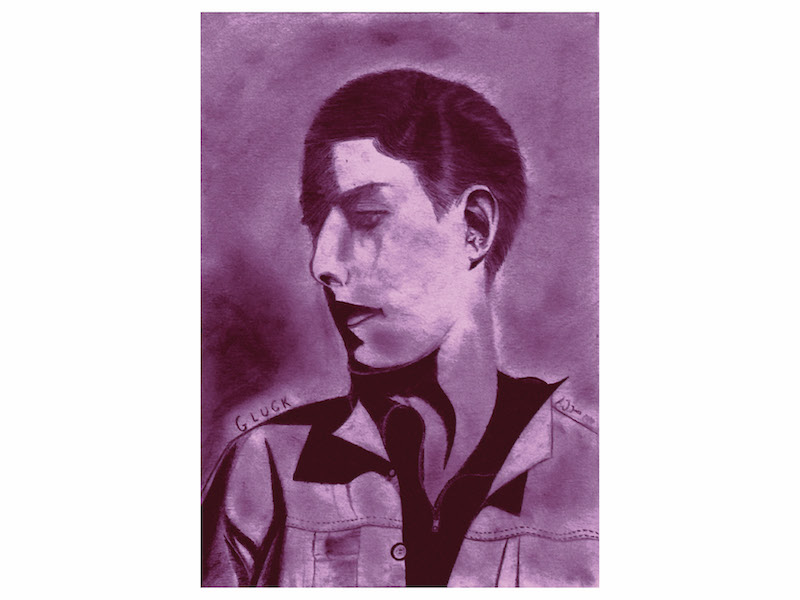

• A series of illustrated biographies, printed on large postcards, depicting notable transgender figures throughout history, as well as certain events or locations relevant to trans history in Britain and overseas.

• A collection of posters featuring trans-positive artworks and slogans.

• A small collection of badges – including a pronoun badge (He/Him/His; She/Her/ Hers; They/Them/Theirs on request) – and other treasurable trinkets produced by a variety of collaborators and project partners.

‘The Gender Chest’ is, at its heart, a product designed to help young transgender people navigate the often terrifying prospect and process of coming out of the closet, and overcoming the considerable challenges that can be posed by the early stages of social, medical or legal gender transition. We want to provide them with a tangible connection to queer and trans histories, communities and support networks. A physical symbol of solidarity, compassion and love from established organisations, support networks and individuals within the LGBTQIA+ community. Vulnerable trans adolescents and young adults need love and solidarity.

However, it is also a project to help friends, family and teachers better educate themselves with regards to trans issues and bodies, helping them become understanding and compassionate advocates for their trans pupils, peers and loved ones. By working through resources alongside transgender individuals, addressing questions as a group, a bigger support network can be created.

Finally, ‘ The Gender Chest’ is intended to be a vessel for one’s own personal archive of transition. It is a storage space for a personal museum of treasured objects amassed throughout coming out and transitioning. These archives can then be compiled online into a decentralised museum, telling the story of the contemporary trans experience –open all hours, and accessible to all, regardless of location. This final element of the project is heavily inspired by E-J Scott’s curatorial project ‘The Museum of Transology,’ which has yet to find a permanent home after its temporary exhibition space in Brighton closed in January. This will help address the need for a museum dedicated to trans bodies and lives until a permanent, physical space addressing that need could be established.

Why do you think it is so important for young transgender people to feel connected to queer history and to have access to queer support networks?

Without a wider network, is it so much harder to process your feelings and feel secure enough in your identity as a trans person to come out and start transitioning in any small way. Without knowledge or awareness of queer issues, or reassurance that the sorts of thoughts and feelings you are struggling to cope with are common amongst a whole community of people, young people will struggle, ending up feeling alone in a solitary struggle.

Having grown up attending an all-boys’ schools and never being introduced to the notion of queer identity outside of brief mentions of gay people in PSHE classes, I felt immensely confused, distressed and on occasion terrified of the behaviours of my cisgender peers. I would have benefitted immensely from being introduced to queer history, to the existence of queer people beyond just gay men and women, and from being made aware of the sorts of feelings trans people experience whilst questioning their gender, coming out, and proceeding with their transitions.

Queerness, unlike ethnic minority identity for example, is not something passed down from parent to child. A young queer person cannot trace their ancestry and history along a family tree, or trace it back to a homeland in the same way a young person of colour has the potential to. Although I must clarify that this is not to downplay the difficulties that can arise in tracing or retelling minority ethnic histories. Having a connection to a community of people progressing through the same challenges you are, and to historical narratives, archives and dialogues collected and determined by a community, is so crucial for a member of any marginalised group. Particularly for an individual queer person, for whom these connections may not be so obviously tangible amongst family, friends or neighbours.

Do you think that the current context (COVID-19) has made it more difficult for young transgender people to access these support networks? Are there any online networks and resources that people can turn to?

First of all, I think it is worth stating that the most worrying thing to come out of the COVID-19 crisis for young trans people is the fact that, while the country’s energy and attention has been distracted by the public health emergency, Liz Truss – the current Minister for Women and Equalities – has stated her intention to legally prevent under-18s from being able to access gender-based healthcare, and potentially enshrine in law the right of individual organisations to ban trans people from single-sex spaces corresponding to their gender identity. In the long run, this could make it nearly impossible for young, vulnerable trans people to seek the help they need, if these comments are representative of any policy direction the current government wishes to take. Even though we have not been able to leave our homes, trans people have been airing their grievances about the Equalities Minister’s comments, and I think I speak for the entire UK’s transgender community when I say that anyone even vaguely supportive of trans rights should do likewise, in any small capacity they can.

Returning to the question, doubtless, there are online resources transgender people of any age can turn to for assistance, regardless of circumstances. Many queer organisations and charities have taken to platforms like Zoom in recent weeks, in order to help deliver their services to those who require them, being unable to deliver support groups or counselling sessions in person. As support groups can be nerve-wracking places for trans people at the beginning of their journeys through transition, in some ways it has become easier to access certain resources, networks and communities, even though the ability to meet and socialise face-to-face has been lost. This is not to say that these virtual services are a valid replacement for physical, face-to-face socials or support settings, but they are a useful complement. On the other hand, for those of us who live in familial homes amongst parents and siblings to whom we are not yet out, participating in support groups over platforms like Zoom would be an impossibly scary act to contemplate. The possibility of a family member overhearing an online conversation that then led to an inadvertent outing means that virtual networks are far from an infallible answer to accessing gender-based support and guidance.

Contrastingly, ‘The Gender Chest’ is designed to assist young trans people who are desperate for a physical, tangible connection to community and who cannot seek support elsewhere, which virtual settings cannot provide. Though online resources can be useful, ‘The Gender Chest’ is intended to be a treasured possession, a symbol of support that can be touched, held and felt in the absence of the ability to access physical manifestations of queer community.

Throughout the early stages of coming out and transitioning, trans people, from my experience, will typically treasure anything that affirms their gender identity and demonstrates that someone out there cares for them. The ‘Gender Chest’ will support them on their journey, it will fight for them. For example, on my desk I have framed a piece of old wrapping paper, because scrawled on it in cheap Biro pen is the first instance of anyone else addressing me by my chosen name in writing. Full of gender-affirming supportive artwork, collectable trinkets, and painstakingly illustrated letters and postcards, ‘The Gender Chest’ provides a young trans person with a whole host of objects that can be treasured, and a storage space for their own archive of souvenirs amassed throughout transition. ‘The Gender Chest’ is also designed to help the family units, friendship groups and teachers of any given young trans person learn how best to help them deal with their emotions surrounding gender and transition, and any challenges of transition, in a way that many virtual support groups might struggle to replicate.

How can people support your project at this time?

As I establish ‘The Gender Chest’ project, I will be producing prototypes of the Chest itself and everything within it. I will be looking for artists to assist me in producing illustrations for the collection of biographies I will be writing for the project, as well as with producing designs for badges, amongst other things. I will be posting more information about these open calls on my website and Instagram account soon. All contributing artists will, of course, be paid for any work provided.

Additionally, as I was previously funding this project’s initial stages through working front of house at a theatre (which has obviously been forced to close of late), I may need to call for donations to support the project and cover my costs. Though ‘The Gender Chest’ will eventually manifest as a charitable organisation, I have been reluctant to make any efforts to crowdfund or seek donations before a full prototype of the Chest itself is complete, but, due to current pressures, I may have to seek donations earlier. Again, details of any donation drives will be posted online.

In the meantime, any efforts to boost awareness of the project via word-of-mouth, via social media or any other means, would be greatly appreciated.

Why did you choose to make this a collaborative project?

I didn’t decide, particularly! It was just a natural consequence of the project’s size and scope, and the scale of expertise needed to pull it off. However, that is not to say I would not have sought collaboration, as I always wanted ‘The Gender Chest’ to be an object created by the queer community, for the queer community. I am particularly indebted to my close friend and long-term collaborator Marlowe Mitchell, whom I have advised on a number of performance projects and for whom I will hopefully be appearing in a series of short films later this year. Marlowe provided me with access to their own immense queer history archive at the beginning of this project, and has used their connections with queer charity London Friend to advise me on ways of making the Chest as user-friendly and useful as possible for its intended audience. Similarly, I am immensely grateful for the support of fellow trans artist Benji Sanger, whose experience of attempting to come out as a trans man in a tiny working-class village in the Fens inspired the initial concept. Also to the Goldsmiths Centre for Queer History, who have offered to assist with project research as well as a whole host of professors and tutors at Goldsmiths, who have continued to dedicate so much valuable time to advising me following my graduation last summer. Of course, I also look forward to collaborating with anyone else who answers my open calls, and indeed with any other supportive organisations in the future.

What are your plans for the future and is there a message that you would like to share with others?

In terms of planning for the future, I have sought to start as I mean to go on in terms of producing ambitious, wide-reaching, long-term projects (which may, as my old A-Level Art teacher often used to warn me, be a little over-ambitious, not that that’s ever stopped me attempting anything before). I hope that, despite the immense setbacks COVID-19 has forced upon us all, I am in the process of sowing the seeds of a long and fruitful career as a storyteller and a non-profit social entrepreneur.

As for my message to others, it is simply this: life as a transgender person in the UK remains extremely difficult despite the immense advancement in awareness of trans people’s existence and their issues in recent years. Healthcare is extremely challenging to access, due to GPs having little to no knowledge of transgender-related medical issues (to the point where I have spent whole appointments teaching my own GP the absolute basics of male-to-female hormone replacement therapies), and by an incredibly obsolete and overloaded NHS Gender Identity Clinic system, whose waiting lists can be upwards of two and a half years between referral and first appointment.

Trans people in the UK are still disproportionately subjected to violence, abuse and harassment, in public and in private. Much of the UK media remains ambivalent to trans issues at best and actively hostile towards us as a population at worst. Multiple trans-exclusionary activist groups and individuals remain devoted to malicious campaigns against the rights of trans people. Even trying to commit an act as simple as using a public toilet is made extremely distressing due to the fact that the whole world has been constructed around a model of binary sex, into which we do not fit.

I would implore anyone reading this who is not themselves transgender to seek the voices of trans people, in this country and overseas, and listen. Put yourselves in their shoes, imagine what life must be like for them, and put that empathy to use by standing up for our rights as we would stand up for the rights of any other marginalised group – in whatever small way you can.

If you would like to find out more about ‘The Gender Chest’, follow Abigail on Instagram.