Bow Arts talks to fine artist and educator Damien Robinson about the intersection of her practice and work with schools, and the importance of embedding curiosity and imagination in learning.

Hi Damien! Could you tell us about yourself and your artistic practice?

Hi, I’m Damien.

I’m a fine artist working with digital and found media, mixing simple analogue approaches with higher-tech equipment and strategies. I now live in Southend, but lived in East London for many years, and still have a strong connection to the area via family.

What do you want people to take away from your work?

My aim is to give people an opportunity to share my curiosity, and to look at things from a different perspective, particularly as that relates to equality and equity. That’s not always obvious; the connections between (for example) works that translate data into shape and colour, intersectional feminism, and Deaf rights isn’t a straight line, but they share a conceptual wellspring.

I’m also a great believer in hidden/sneaky learning. I believe that people will remember and absorb creative messages – and creative learning – much more effectively if they have enjoyed themselves.

I aim to include elements of fun, pleasure, and even silliness rather than to pontificate. One of my favourite bits of feedback from a student was “I didn’t know we were actually learning because it was so much fun.”

Damien Robinson

Damien Robinson/Ruth Kathryn Jones, 2019. Risograph printed artists edition of 50. Published by The Old Waterworks, supported by A-N. Image credit: Anna Lukala

You mention that in your personal practice you combine digital and found media, as well as contemporary and historical technologies. In what ways do you adapt these tools of creating to your learning practice in school settings?

I’m always fascinated by how young people learn about and react to older technologies. I’m not a digital native – I grew up without computers and mobile phones – so I love showing young people pre-digital strategies for creative use.

For example, the processes and science that led to the development of photography, film, and animations – which we take very much for granted – are all new to them, and they allow young people to be hands-on, dexterous and tactile in ways that digital media usually bypasses. Combining these methods with digital approaches can embed that earlier knowledge into their digital native world rather than it remaining as something from history.

Most recently within an Explore Arts Award, we made mini-kaleidoscopes and filmed what we saw through them using a mobile phone, thus bridging the old and new technologies and making sharing and celebrating their work much more straightforward.

However, my favourite response to the use of old tech came from a project where we made spirit levels for tiny model buildings; “How do you get the bubble into it???”

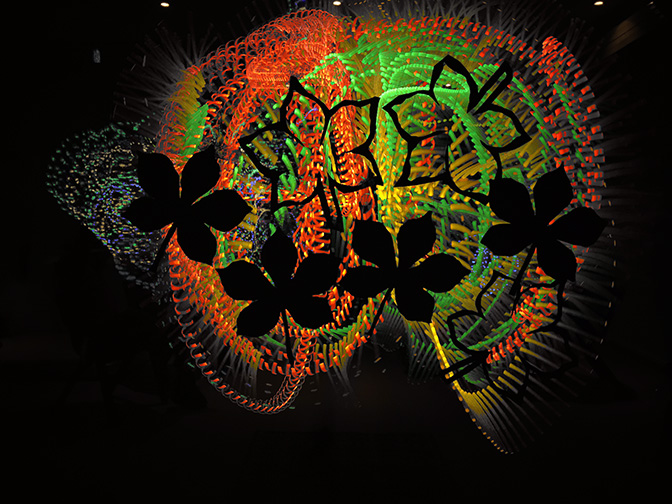

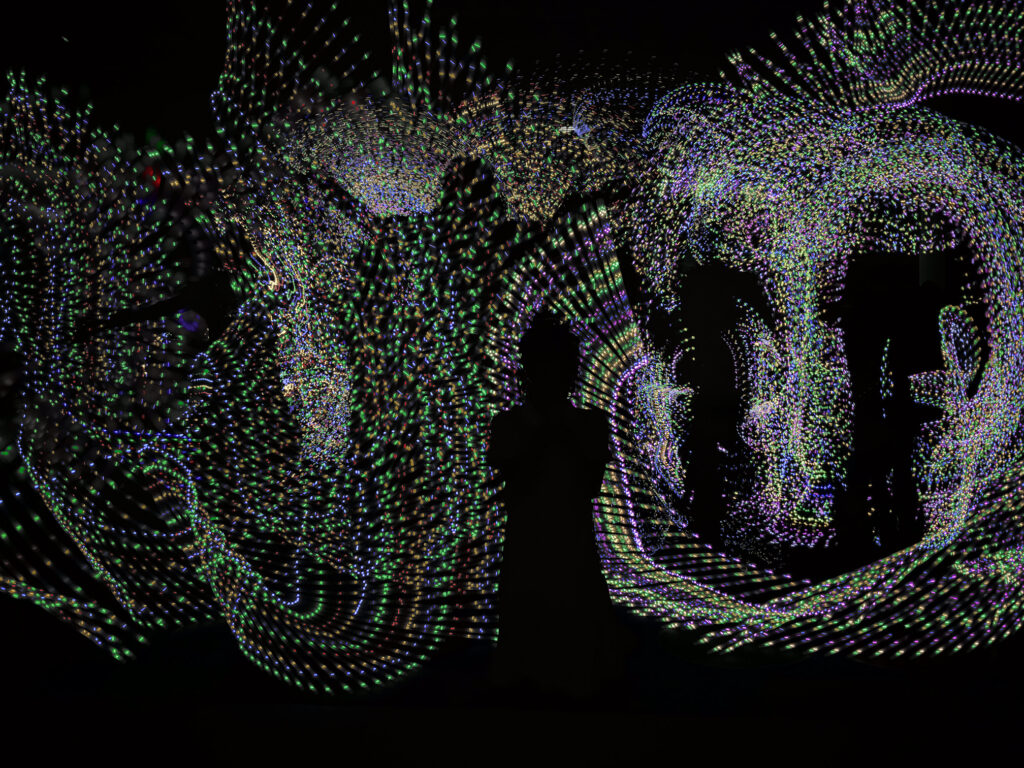

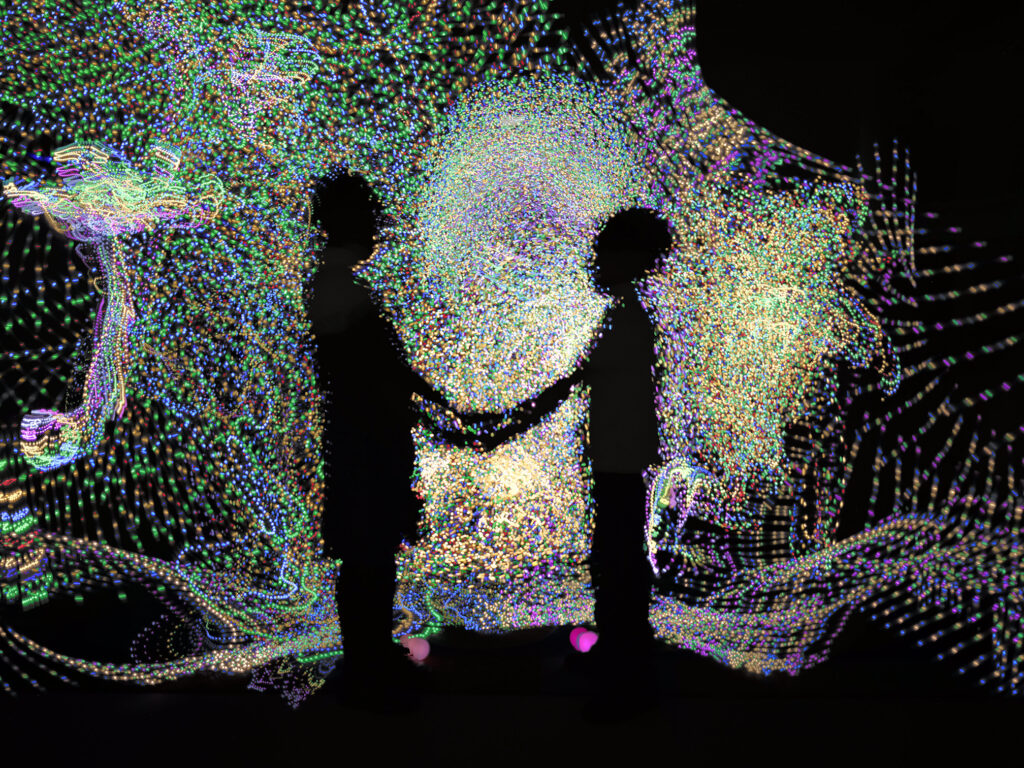

You have developed an accessible photography method, ‘Painting with Light’, which you have tailored for a couple of Bow Arts school projects during your years with us as an artist educator – most recently for a process-led commission at Beam County Primary in Barking & Dagenham. Could you give us an insight into the process of developing this workshop?

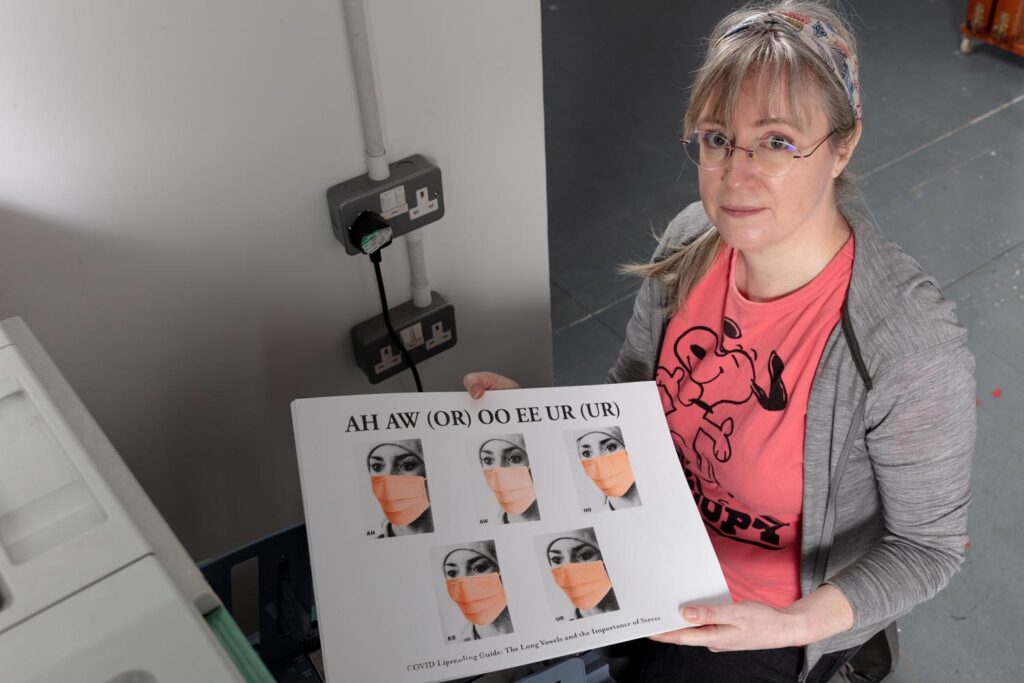

The process evolved from an NDCS workshop with D/deaf young people where I was asked to try out light painting (which I’d never attempted before) within an indoor space. Although we got some great images, as deaf people, we couldn’t communicate in darkness, and the regimented approach (for safety reasons) felt deeply unfair.

Afterwards, I started experimenting with adjusting light levels inside the camera rather than using a blacked-out workspace and discovered that this provided a more equitable environment where individuals could explore their creativity and have fun. It’s taken many years of experimentation and play to develop the process, and every workshop refines the approach through the experiences of the people I work with.

I make the majority of the (low cost) light tools myself, a mindset embedded from Mongrel and YoHa, artists I worked with at MediaShed where the ethos was “replacing money with imagination.” A constant within my practice is ‘misusing’ processes and technologies – often through lack of access to learning mechanisms as a deaf artist – so I’m often told “You’re not supposed to do it that way!”

Going down the ‘wrong’ path can result in some unexpected successes. With daylight light painting, experimenting is part of the process, so there is never a wrong way, it’s all about ‘let’s see what happens’.

Damien Robinson

Could you share a favourite moment from a Bow Arts project you have been involved with?

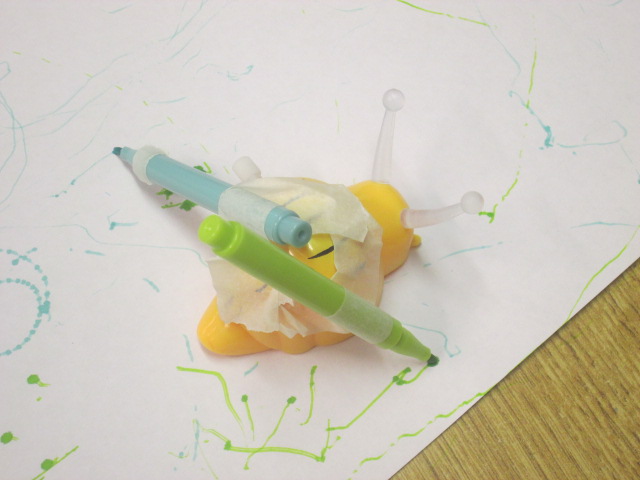

There have been many lovely students I’ve worked with, so it’s a hard choice. But I think the first project I delivered for Bow Arts, which involved multiple year groups making ‘draw bot’ drawing machines and making large scale collaborative bot drawings, helped me understand I could show students something of the breadth and depth of creative practice.

I was told one student usually hated art lessons and refused to join in, but he loved the draw bots because he could integrate his maths and science preferences, and still be creative.

Damien Robinson

Could you tell us about your journey of becoming an artist working with schools?

I first worked in a school as an offshoot of a Deaf-focused new media project. Through that placement I discovered that I enjoyed working with young people and began looking at how I might expand my knowledge and experience. I then undertook postgraduate professional practice training at the Institute of Education, specialising as an artist working in schools. This gave me both a practical and theoretical grounding which allowed me to consider this area of work in a more holistic way. Artists often get ‘parachuted’ into education settings which can make relationship building more challenging, but relationships are the foundation of what you do.

Since then, I’ve worked with a wide range of galleries and creative organisations on their learning offer, working with people of all ages. Working with Bow has also given me contact with several participants from your Trainee Artist Educators programme, so as I’ve learned from other people, hopefully I’m in turn able to pass on knowledge.

How would you say your learning practice impacts your personal practice?

It’s circular – I mentioned that I want people to share my curiosity, that is where my creativity stems from, but connecting with learners (of any age) means you’re also exploring through their perspectives, and they’ll take approaches you haven’t thought of or ask questions you’ve not considered. So I get to see what I do through fresh eyes, and what connects (or doesn’t).

You also get to see the response to your abilities and knowledge – it’s easy to forget that you know stuff because it’s your baseline, your normal. And it’s your job too, so bringing it back to being fun recharges your own batteries.

Do you have any tips for educators who may be reading this?

Never be afraid to say ‘I don’t know‘ and ‘What do you think?‘. Creative practice is about exploring together, not about having all the answers and being the ‘expert’. We want young people to understand that experimentation doesn’t immediately result in success, but that what might look like failure in the first instance is often a new pathway to understanding.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on the design element of the Beam County light painting project. We got so many fantastic images; the school is going to have a huge challenge deciding which ones get used in the final work. They were fantastically supportive and attentive to my suggestions, and we also had parents involved in the final sessions which was very special

I’m also working on a participatory project with Essex Records Office, exploring Southend’s Deaf history; again we’ve found out a lot, so producing an outcome is going to be challenging! And I’m back at the British Library in September for their Deaf families day, an annual and wonderfully accessible event – can’t wait!

See more of Damien’s work on her website, and follow her on Instagram.

About Damien Robinson

Visual artist / Educator

Damien Robinson is a deaf visual artist based in Southend-on-Sea working with digital, print, and found media equipment and strategies. Her work was originally print-based; based on children’s stories and toys, it was exhibited in venues as diverse as phone boxes and the National Art Library. Her practice developed through new media experimentation, influenced by work with artist collectives (including MediaShed) and their open approach to technical and creative participation. She has developed works for traditional gallery spaces and less conventional environments; from wildlife reserves to fire training towers to maternity wards. Repurposing and misusing processes and technologies (often through lack of access to learning mechanisms as a D/deaf artist), allows her to discover new processes and outcomes.

In addition to her creative practice she has worked as an arts project manager, business development advisor and researcher. She worked as an ACE officer from 1997-2006 in education, employment and resource development specialities. She is a trained mentor and an alumnus of the SSE (School for Social Entrepreneurs) Creative Leadership programme. She is also a founder member of The Agency of Visible Women, an intersectional women artist’s network in South Essex, and Flare Arts, which supports sustainable cultural change and challenge barriers by upskilling deaf creatives.

Damien has exhibited nationally and internationally as an individual and with collaborative works at Focal Point Gallery, Banff NMI, Ars Electronica, Metal Culture, Beecroft Art Gallery, and TOW. She has developed commissions and digital engagement projects for organisations including Commissions East, Firstsite, ACAVA, Bow Arts, Studio 3 Arts, Space Studios, Photographers Gallery, and Essex County Council. Online works have included commissions (iniva) and exhibitions (Shape Arts), plus residencies for PVA Medialab and Vital Capacities.

Painting with Light at Greenvale School

Six Greenvale Primary School students collaborated with visual artist Damien Robinson to create a striking window artwork for their school.